Foundational Beliefs

(This section is purely philosophical. If you’re looking for the nuts-and-bolts of how this game is different than Second Edition Pathfinder, (the root system this game is built on,) please skip to the “Magic” section and read from there.)

There are as many approaches to tabletop gaming as there are groups of people playing. The structures of the game systems we use inclines us towards styles of play. So for example, having a 650-page tome of finely-calibrated rules that attempt to define, limit, and empower every possible situation has inclined many players to believe that they should play according to the rules in that book. For groups with this mindset, a large part of roleplaying is the construction and playing of a highly refined mathematical representation of their character, with some accents or dialogue peppered in here and there for flavor. Very few groups would phrase it this way, but if you look at how they spend their time at the table, this description is accurate. A lot of time is spent crunching numbers and rules, which is why this play style is often described as “Crunchy,” (or “Hack-and-slash,” due to the inherent emphasis on damage that arises from numbers-heavy gaming styles.)

Other groups are more interested in the narrative, the drama. This style of play tends to involve more cinematic roleplaying, where the backbone of the experience is the acting of the character, and the math is used to support the narrative. One of the best GMs I ever played with was an old man who started playing DnD in the 70s, and as a GM he used absolutely nothing. No notes, no books, no screen, no dice. He simply sat at the table and described what happened. We rolled dice, and that informed outcomes, but there was zero lag in the game. He simply told us if we hit, and would say things like “Great, the log you rolled killed a few orcs, but more are coming up the hill.” That was one extreme of narrative play.

Both have pros and cons, and basically all games exist somewhere on this spectrum.

Some people really love crunchy, hack-and-slash gaming, where the experience is basically encountering one monster after another, killing them with damage-optimized attacks as-per the rulebook, and leveling up. There is nothing wrong with that, if you’re all having fun. The upside is that crunchy play is very, very fair. Both the players and the GM are bound by the same rules, and subject to the same expectations. So if the GM wants a Troll who can swing a tree and hit everyone in the party, they have to build a troll who has multi-classed as a fighter, taken a specific set of feats, has particular proficiencies, and can beat each player’s AC with a set of consecutive attack rolls. If the Troll fails any of their attack rolls in sequence, including penalties for multiple attacks, then it does not hit the next character in line. That is mathematically fair.

There are two large downsides. The first is that it can be brutally slow. Both players and the GM must look up rules for specific situations, and the math can be intensive, so a single round of combat can take a very, very long time, and it is not exciting time- it’s page turning and adding up sums. This is so normalized that it is considered normalized that it is considered inherent to tabletop gaming. It has lead to DnD being called “30 minutes of incredible fun packed into five hours.”

The second downside is that by it’s nature, this emphasis on the mechanics pulls people out of the roleplay. It is a very particular skill to be able to quickly step back and forth from the mathematical/hyper-logical part of the brain required to understand the math of a rule or mechanic of a spell and then jump right back into embodying and roleplaying an emotionally charged situation for your character. That acts as a massive barrier for people really roleplaying, so the gaming experience ends up being much headier and less narrative.

The downside of more narrative roleplay is that it is not as consistent. At the extreme of the example I mentioned earlier with that older GM, it is guaranteed to provide inroads for the GM’s innate prejudices and biases to slip into the game mechanics. It cannot be as objectively fair as a crunchier game.

It has many upsides, though. The first is that it is intuitive. Rather than looking up what your character can do based on a specific ruleset and then deciding what their character should do based on the math and rules, players simply say what their characters do, and then the dice and the GM tell them how that goes. For the same scenario with the Troll, in a more narrative-focused game the GM would simple say: “The troll swings his log at your whole group. Everyone gets a reflex save to dodge.” There is no expectation that the GM or anyone could lay out the mechanical details of how the troll is performing this attack- it’s just an intuitively accurate thing that a troll can do to swing a log at a group of people.

The second is that it is fast, and therefore much more engaging for a more diverse group of minds. Crunchy games with a lot of in-game rules-clarification are accessible as “fun” to very specific type of mind. Narrative play which is faster-paced and more intuitive is accessible to a different group of mind-types, and as such makes gaming more diverse.

At it’s core, the value of narrative play is that it creates the space for the creation of a richer and more coherent narrative. The point is the story we are making together, not the mechanics.

I make no effort to conceal my preference here- I prefer more narrative roleplay these days. On a scale of 1-10 with 1 being crunchiest and 10 being most narrative, I’m like a 7 or 8. I don’t want to decide if characters hit enemies or whether enemies hit characters- I’ll leave that to my notes (monster builds) and the dice. But as soon as it would take me more time to look up a DC in a chart than to make one up, I’ll make it up, because it keeps the game moving.

This desire for more intuitive, narrative play is the root of all the homebrew modifications listed below. Open initiative and unbounded magic are just ways to remove barriers to consistent roleplaying.

Magic

Overview

There are two types of common magic in to’Ren. The first, oldest, and by far the most powerful is natural magic. This is magic cast from a connection to the natural world, or a part of the natural world. Natural magic is custom, meaning that spells are created in real-time based on the situation. It is dynamic and reactive. The application of this magic is syntactic, meaning that it uses the relationship between words of the Old Tongue to direct forces. The practice of this is almost always a noun verb combination in conjunction with hand gestures that describes what one is doing, and directs it. So one could simply hold out their open hand and say: “Creo Fuego” and call fire into one’s hand, or point at someone and say “Tu quemas” to ignite them. For area magic, this is often implied. For example, looking around a room and saying “Revelar” will show things that are hidden or invisible. (More on the mechanics of that to come.) For everyone outside of the Empire, this is simply called “Magic.” Within the Empire, this is often called “Druidry,” “Trickery,” “Dirt Magic,” or any number of other less flattering sobriquets.

Within the Empire, one finds the other form of magic, known there as High Magic, or Formal Magic. High Magic is perfectly reliable, and can be practiced by anyone with the patience, diligence, and intelligence to study and learn spells. Within the Empire, this is framed as “the people’s magic,” “egalitarian,” and “free.” High Magic is predictable and quantifiable. Because of this, is it also scalable with industrial means. The backbone of the Empire’s power is the industrial scaling-up of High Magic. The limited degrees of air and space travel, their weaponry, their tracking systems, are all scaled versions of High Magic. Outside of the Empire, this magic is referred to as Bound Magic, Human Magic, Slave Magic, and any number of other less flattering sobriquets.

It is noteworthy that while judged and frowned upon, there are many High Magic users actively working within ale’Keli and all throughout the free territories. The magical defense system that protects ale’Keli is built on High Magic. So while High Magic users tend to keep their magic to themselves in Keli, they are present and valued. People outed as High Magic users tend to face some stigma and scorn.

Mechanics

High Magic functions “Rules As Written” within the Pathfinder 2e ruleset. Empire wizards are PF2E wizards.

Natural Magic functions as follows:

Primary Magic Users (Witch, Sorcerer, Druid, etc…) can manipulate matter. The degree of precision and damage that they can summon scales with their levels. Some tasks will exceed their capacity, for example if a 1st lvl Witch tried to pick up a house, the Difficulty of that task would be higher than she is capable of, so the house would not move. Nuts and Bolts, the Difficulty of a given task is measured as “Difficulty Class,” a measurement of how hard a given task is. Picking up a pen would have a DC of One. Picking up a house might have a DC of 28. Picking up a city might have a DC of 60, and would thus only be possible at very high levels or with a lot of help.

Proficiencies

Primary Magic Users can add their Proficiency Bonus (under PF2E Rules) to their casting.

Beyond that, they can choose a Focus. This can be an elemental category of magic, such as Fire, Water, Earth, Air, or Spirit, or an effect of magic, such as Healing, Environmental Control, Concealment, Damage, or any other focus they choose. They are considered “Trained” in that focus, and proceed to “Expert,” “Master,” and “Legendary” as delineated in PF2E.

Spellwork of Natural Magics

For natural magic:

Spell slots follow the Spell Slot charts in PF2E. Spell levels are determined in-game based on the context and task being attempted.

For Damage, the baseline is:

(Spell Lvl +1) + (1 per every 3 Caster Levels) = # of d6 of damage.

So if a 1st level Druid wanted to burn a guard, she could choose to cast that as a Cantrip (a zero-level spell,) which would do 1d6 of damage, or as a 1st level spell, which would do 2d6 of damage.

Once she is lv 3, the same cantrip would deal 2d6 of damage, and the same spell cast at Lvl 1 would deal 3d6 of damage.

Generally speaking, Cantrips use one Action and all other spells use two Actions (within PF2E’s 3-action per round economy)

Assists

Magic users can assist one another in casting. The spell level becomes the sum of the spell levels cast x 1.25, rounded down. This means that if a character casts a 2nd-lvl spell, and another character assists them with another second-lvl spell, they collectively cast a 5-th lvl spell.

The Law of Entanglement

“Once whole, always whole.” Simply put, if you have a part of something, it can be used to affect the whole of the thing. For example, if you have a strand of someone’s hair and put it in a fire, you can cause their head, or their whole body, to warm with minimal effort. The degree to which you can warm them is contingent on your spellcasting level and the spell level that you use, and ranges from imperceptible warming up to the heat present in the source fire. So a lvl 5 caster who has a hair from someone without any magical protections and a blast furnace can incinerate that person.

Entanglement is not distance-contingent, making it exceptionally useful for tracking.

The Law of Sympathy

“Like affects like,” or “Birds of a feather.” Magically, you can make a fire larger. But if you have a flame in your hand, it is much easier to manipulate another fire. Because of this, spellcasters will often pick up a “contact” of whatever they are working to manipulate. So a sorcerer who wishes to shake the earth underneath a group of archers nearby would be foolish not to pick up a piece of earth from under their feet, as it will make the task much easier.

Sympathy degrades over distance, so using a pebble to try and lift a stone in front of you is fairly easy. Using it to lift a stone 20 miles away is extremely difficult.

The Law of Proximity

The easiest magic is always magic done on one’s self. Beyond that, magic is far more powerful if the caster is touching the subject. This means that a healing spell cast while touching someone is more powerful than a healing spell cast 10 ft away.

If a caster wanted to freeze someone, for example- by far the most powerful setup for this would be the caster touching something brutally cold with one hand and touching the person with their other hand. In this way, the caster can act as a conduit for the cold without the loss of transferring the cold through the air.

Feats

The Feat system in PF2E still applies, but it will take some conversion for some of the feats to make them make sense within this approach to magic.

Credits

This system of Syntactic magic is built from GURPS Thaumatology, with some elements of Ars Magica 4.0.

…it’s alive!

All of this is a work-in-progress, intended to minimize the sheer memorization and player study barriers to playing Magic-users. It’s also a much looser ruleset than the rigidly-defined rules of Pathfinder as written, so it’s guaranteed to be less balanced and we’re going to have to make sure to be balancing it as we go. The upside is that it liberates your magic. You can try and do whatever you want to do with your magic. If it’s something you’re practiced in, your odds are better. If you have help, your odds are better.

Regardless of this un-bounded magical system, it is well worth reading through the spell lists of your class, for the sake of getting an idea of how to use your magic. This is by no means a requirement, the point of this system is that you don’t have to know anything or memorize what spells you have, but it will give you a wider sense of the possibilities and options you have.

Stats

Imagine, for a moment, that you show up to a session zero you’re asked to roll stats for the following: Devotion, Piousness, Political Influence, Dependability, Craftiness, and Physicality. What do you already know about that world? What do you expect that campaign to be like?

Stats are not a neutral measurement; they are a value indicator. What we choose to measure as our core statistics says a great deal about our characters and more importantly about the world that they inhabit. While the classic Str/Dex/Con/Int/Wis/Cha stat block has the strong benefit of familiarity, it has the extreme detriment of being inherently limited and defining a campaign as within a lineage of a very particular value set.

Beyond this, the classic stat block has strong drawbacks in terms of intrinsic consistency. For example, in classic D&D, sorcerers are Charisma-based casters. For this to make any sense, one has to stretch the word “Charisma” far past the breaking point. Examples of these glaring inconsistencies abound.

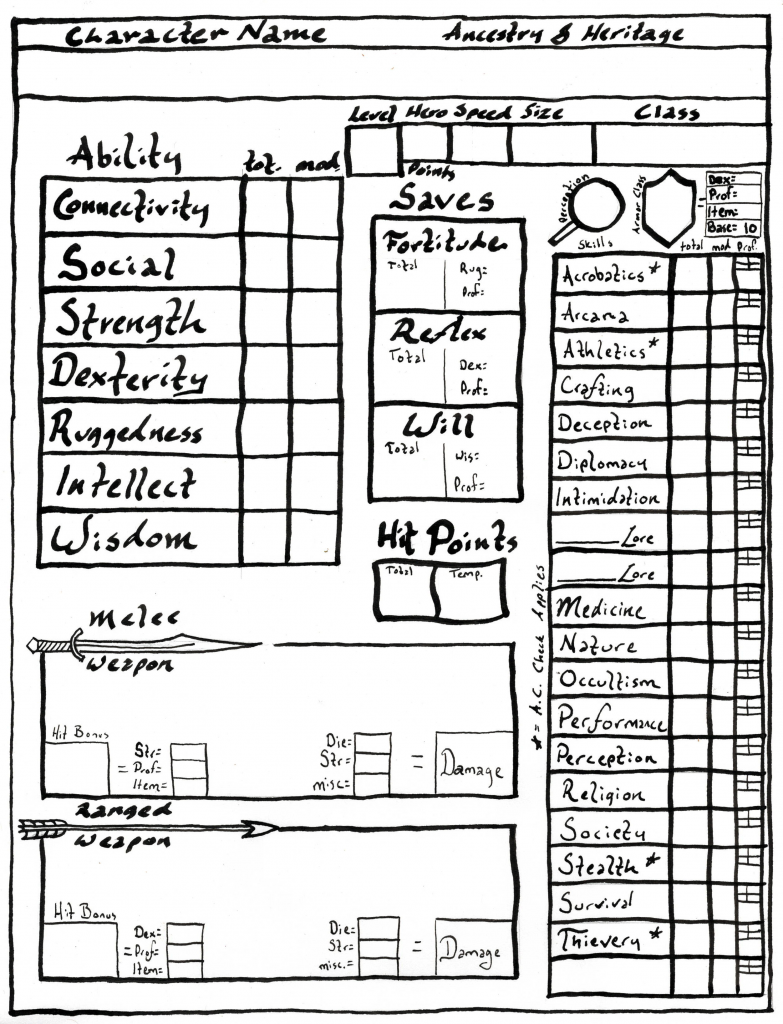

So for this campaign, we operate from the following stat block:

Connectivity (Onn)

Social (Soc)

Strength (Str)

Dexterity (Dex)

Constitution (Con)

Intellect (Int)

Wisdom (Wis)

Most casters outside of the Empire are Connectivity-based casters. As with all stats, this takes different forms, for example a Druid is casting based on their connection to the natural world. A sorcerer is casting based on their connection to their own ancestry. (Note that this connection to ancestry need not be healthy- but it remains the source of their power.) A Witch might be casting based on their connection with their familiar.

There are some Intellect, Wisdom, and Social based casters outside the Empire. The famed engineering gnomes of Quirk, for example, are Intellect-casting Wizards. Some Monks are Wisdom-based casters, while others are Connectivity-based.

Casters within the Empire fall into two categories. The first, and by far the most common, are Wizards. Wizards cast from Intellect, and draw their power from their study of magic, through an academic and institutionalized lens. The second are Clerics and Paladins. The Empire is emphatically, militantly monotheistic, worshiping “The One True God” and despising, denigrating, and destroying all other forms of worship. Their “One, True God” is Atriox, though he is generally referred to only as God. Most Clerics and Paladins of the Empire draw their power from their relationship with Atriox, and as such are Social casters, with a very sharp, exclusive emphasis. Some, however, are not devout at all, and are Intellect casters, despite identifying as Clerics.

Open-Ended Initiative

Instead of each character having their own rigid order in the initiative stack, there will be a group roll for initiative (mechanics at end,) and then it will be either Opponent’s Turn or Ally’s Turn first. Ally’s Turn (your turn) will consist of a series of each of your party’s character’s actions, without any set order. (bear with me!)

The intention of this is to make roleplaying combat more interactive and dynamic. The current mechanics of combat incline it towards a straight slug-fest. Hit, get hit, Hit, get hit. Open-Ended Initiative allows for inter-character negotiation, combo attacks, and planning. As free actions, you can yell things to your party members, such as “Guard me!” as you prep a spell, or collaborative requests like: “Help me cast this,” Throw me,” or “Let’s flank her,” and then both act on this, without the confines of a set initiative order. You have the three actions from PF2E, and each player is still able to use all three during Ally’s Turn, but each of your actions can take place whenever the player sees fit. This means that you can take your three actions in whatever mix of timing you see fit.

While yelling things is a free action, I’ll ask that we try and remember that a turn is 6 seconds. This means that as a group, you have six seconds to plan and execute whatever action you are deciding to take, during that turn. Since the gameplay takes much longer than this, accurately role playing this will be challenging. Beyond this, it will be more tempting to metagame, i.e. “but if I go over there, Cora won’t have a clear shot with her bow!” Recognizing and yelling that audibly would take about 6 seconds: you see the challenge. Within that, you can also continue yelling or whatever you’re doing during the opponent’s turn. While I’d prefer you, as players, not interrupt me while I’m describing your opponent’s actions, your characters can certainly keep making suggestions or whatever while someone from your party gets pincushioned by a fire demon. Time does not actually stop for you while enemies attack. Hopefully, Open Ended Initiative will make this all more intuitive and dynamic. I have a lot of confidence in your ability to swim these deeper waters.

Also; within this modification, you should expect enemies to act with more coordination against you. That’s all the heads up you get; use it wisely.

Mechanics: Character physically closest to enemy rolls Primary Initiative. If party is evenly surrounded, Primary Initiative Roll is made by either character who noticed enemies first, or if y’all are dead surprised, whichever party member makes the highest Dex check. Character’s within 10ft of this character may roll to support. (this means they also roll 1d20, if their roll meets or beats the DC of the Initiative Check, the primary initiative roll receives +2. If supporters roll DC+10 or greater, this yields a +4, and DC-8 or greater on a support roll yields a -4 to the primary initiative roll. There is an expanded Crit Fail on the bottom end because it’s much easier to slow the group down than it is to speed them up. Roll accordingly.)

This mechanic is a combination of the Open-Ended Initiative mechanics from FFG Star Wars and Warhammer 40k Wrath & Glory.

Alignment

Good/Neutral/Evil alignment is a crutch. It can be a useful crutch, many of us struggle to embody ethics other than our own. But it is also a deeply expensive crutch. No one actually thinks of themself as “Evil.” That is not how people make decisions. There’s a quote from an author, I want to say Hemmingway, that goes: “If you can’t explain why your villain thinks they are the hero, you don’t know your villain well enough.” This is the approach we take to alignment; rather than think of your character as “good, neutral, or evil; lawful, or chaotic,” I invite you to simply get to know your character. If you need any reference point, consider their psychology more than their alignment. Are they inclined to see themselves as the victim in hard situations? As the savior? What are they afraid of? What do they want? If you familiarize yourself with these things, you will find that terms like “evil” might apply to other characters from your character’s perspective, but they are not how your character thinks of themself.

Races and Species

This may seem semantic, but it is not. Dwarves are not a “race” of humans. Drow are not a “race” of gnomes. What we are discussing are wholly different species. This terminology helps us deeper understand the fundamental differences between the species who co-exist in to’Ren. For example, Orcs live in strict Honor-based tribes with clear boundaries and hierarchies maintained by ritualized combat. This is an ancient and effective lifeway for them, and works very well within their species. Halflings are a communal agrarian society with loose boundaries between largely overlapping townships. They traditionally practice a hybrid form of Matricentrism and Council Governance, which works extremely well for their species. When Orcs and Halflings interact, it is not the meeting of two different races of one species; their differences are fundamental and rooted in the fact that they are wholly different types of being.

Informed Consent

The purposes of this game are fun and growth. Being unnecessarily triggered by topics arising that you find traumatic without your consent is neither of these. Because of this, we clarify up front what content we are willing to engage with and what we are not. This campaign may include the following potentially triggering content:

-Physical violence with moderate descriptions

e.g. “Your axe cuts clean through the Paladin’s arm, throwing a spray of blood across his squire. He screams, and falls to the ground clutching his abbreviated bicep.”

-Cultural violence

-Slavery

-References to torture and enslavement

-Ecological violence

This campaign will not include the following content:

-Sexual Violence

-Graphic descriptions of torture

Other content to be included or excluded can be clarified with the group.

Beyond these clarifications, we like to make sure people always feel safe with whatever content we are exploring, however mundane. For the sake of this, we use a tool called the “X-card”, which is literally just a card with an “X” on it, sitting on the game board. This card is a tool to make the story-telling both more collaborative and safer. It’s a content veto. If the story, through myself or a player, starts moving into territory that is not going to be fun for you, you can just tap or raise the X card, and as a group, we will not engage with that content. It doesn’t matter why you feel like playing it, and no explanation is necessary. It’s also not a big deal. For example, I have some recent discomfort in my life with navigating hospital’s treatment of elders. None of you have any reason to know this. If your party decided to undertake a long roleplay of navigating health care providers treatment of elders, I might tap the ol’ X card and move us in a different direction, because that would not be terribly fun for me right now. Or, maybe I’d embrace it as an opportunity to process some of my feelings about that, but I’d do it consciously, and with the knowledge that I could veto that content at any time, if I needed to.

To clarify, this card is for player emotions and concerns, not character emotions and concerns. Your characters may have to endure stressful situations or triggers from their past. You do not, in the context of this game, if you do not wish to. I have complete faith in you to recognize the difference.

This mechanic was devised by John Stavropoulos

Character Sheet

XXXX IN PROGRESS! XXXX